The Williamson Ether Synthesis

- In the Williamson Ether Synthesis, an alkyl halide (or sulfonate, such as a tosylate or mesylate) undergoes nucleophilic substitution (SN2) by an alkoxide to give an ether.

- Being an SN2 reaction, best results are obtained with primary alkyl halides or methyl halides. Tertiary alkyl halides give elimination instead of ethers. Secondary alkyl halides will give a mixture of elimination and substitution.

- The alkoxide RO- can be those of methyl, primary, secondary, or tertiary alcohols.

- The reaction is often run with a mixture of the alkoxide and its parent alcohol (e.g. NaOEt/EtOH or CH3ONa/CH3OH). Alternatively, a strong base may be added to the alcohol to give the alkoxide. Sodium hydride (NaH) or potassium hydride (KH) are popular choices.

- When an alkoxide and alkyl halide are present on the same molecule, an intramolecular reaction may result to give a new ring. This works best for 5- and 6-membered rings.

- When planning the synthesis of ethers using the Williamson, take care to select the best starting materials for an SN2 reaction. Avoid planning a Williamson involving a tertiary alkyl halide or a phenyl halide!

Table of Contents

-

- The Williamson Ether Synthesis

- Mechanism of the Williamson Ether Synthesis is SN2

- Primary and Methyl Alkyl Halides Work Best

- Solvent Choice In The Williamson

- Intramolecular Williamson Ether Syntheses

- Planning Ether Synthesis via the Williamson

- Summary

- Notes

- Quiz Yourself!

- (Advanced) References and Further Reading

1. The Williamson Ether Synthesis

One of the simplest and most versatile ways for making ethers is the SN2 reaction between an alkoxide (RO-, the conjugate base of an alcohol) and an alkyl halide.

Although this is a very old reaction - the first report was in 1850! - it just hasn’t been surpassed. It works well for making a variety of ethers and is known as the Williamson Ether Synthesis.

SN2 reactions between neutral alcohols and alkyl halides are generally quite slow. Since the conjugate base of any species is a better nucleophile, the reaction is sped up considerably (Note 1) by employing an alkoxide instead of a neutral alcohol. [See article: What Makes A Good Nucleophile?]

A common way to do the Williamson is to simply use the alkoxide nucleophile with its parent alcohol as solvent (indeed, that’s how it was done in 1850!)

For example, the classic way to make diethyl ether is to treat the ethyl halide (the chloride, bromide, or iodide all work, but not the fluoride) with the ethoxide ion in ethanol.

For our purposes the identity of the leaving group (iodide, bromide, chloride, tosylate (OTs), mesylate (OMs) ) does not really matter, although it is important to know their relative leaving group abilities (See article: What Makes A Good Leaving Group).

Likewise the identity of the alkali metal salt (Li+ , Na+, K+, etc.) does not matter much for our purposes and we will use these metal salts interchangeably.

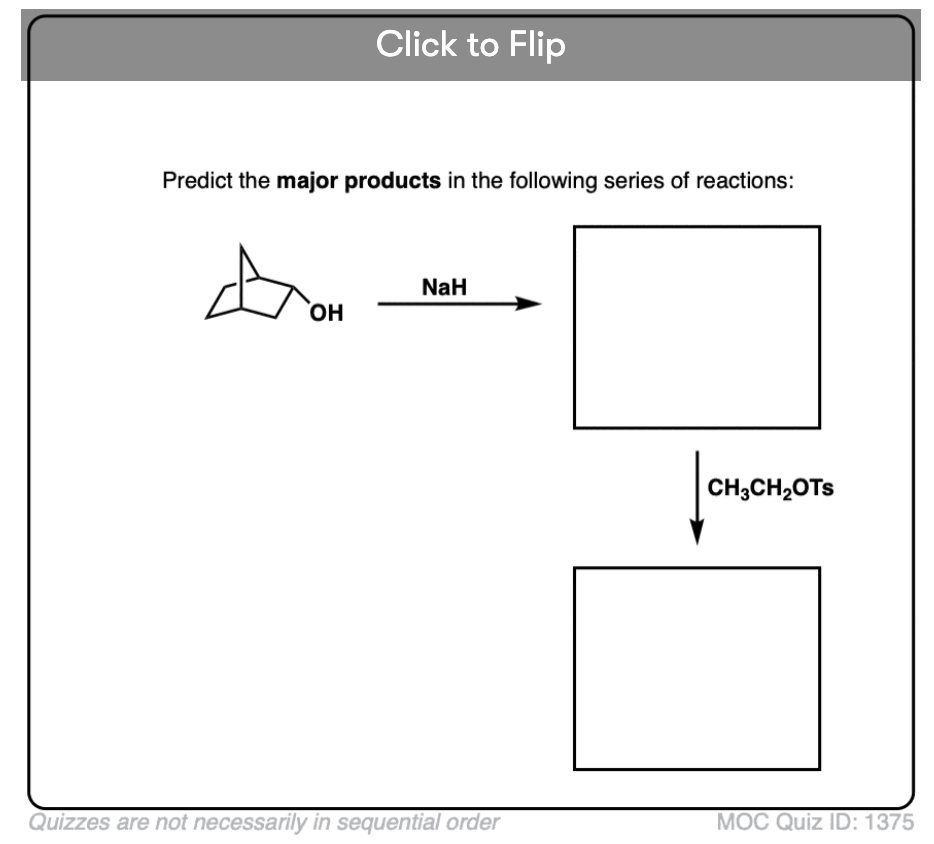

Since it’s not always an option to use the alcohol as solvent, another option is to generate the alkoxide by using a strong base that will irreversibly deprotonate the alcohol.

A popular choice is the hydride ion H- , which is the conjugate base of hydrogen gas (pKa about 35) and is also a poor nucleophile to boot. Sodium hydride (NaH) or potassium hydride (KH) can be added to the starting alcohol to generate the alkoxide. The hydrogen gas byproduct then bubbles out of solution into the atmosphere.

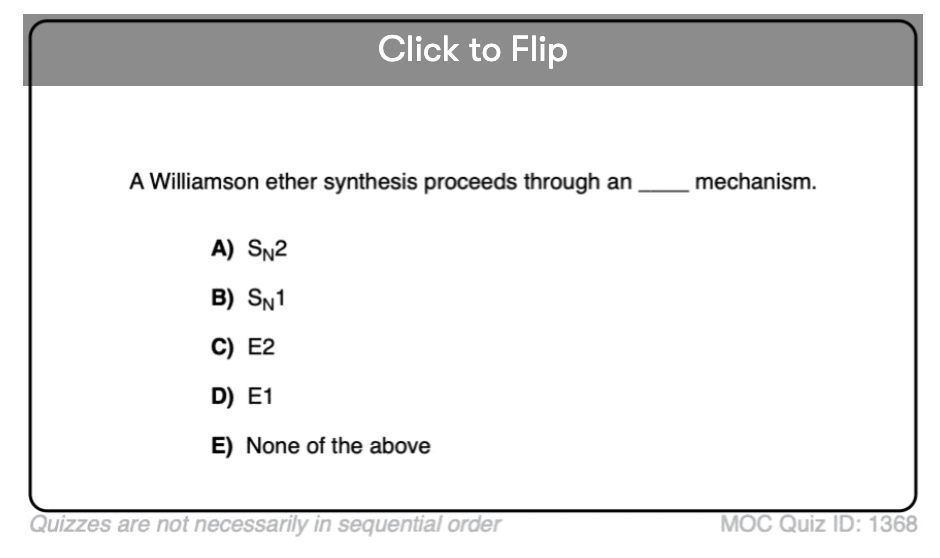

2. The Williamson Ether Synthesis Proceeds Through an SN2 Mechanism

The Williamson ether synthesis is a substitution reaction, where a bond is formed and broken on the same carbon atom. In this substitution reaction, a new C-O bond is formed, and a bond is broken between the carbon and the leaving group (LG) which is typically a halide or sulfonate.

It proceeds through an SN2 mechanism (nucleophilic substitution, bimolecular) where the nucleophile approaches the carbon atom from the backside of the carbon-leaving group bond. (See article: The SN2 Mechanism)

A pair of electrons from the nucleophile are donated into the sigma* (antibonding) orbital of the C-leaving group bond.

This requires that the nucleophile actually makes its way to the orbital on the backside of the carbon! For this reason the SN2 is fastest for methyl and primary alkyl halides, and does not occur on tertiary alkyl halides due to the fact that nucleophiles can’t make their way through the tangled thicket of alkyl groups on the backside. (See article: Steric Hindrance Is Like A Fat Goalie) .

Substitution reactions of alkoxides with secondary alkyl halides can occur, but often occur with significant elimination through the E2 pathway.

In the transition state of the SN2 there is a five-coordinate geometry about the carbon with partial bonds to the nucleophile and to the leaving group.

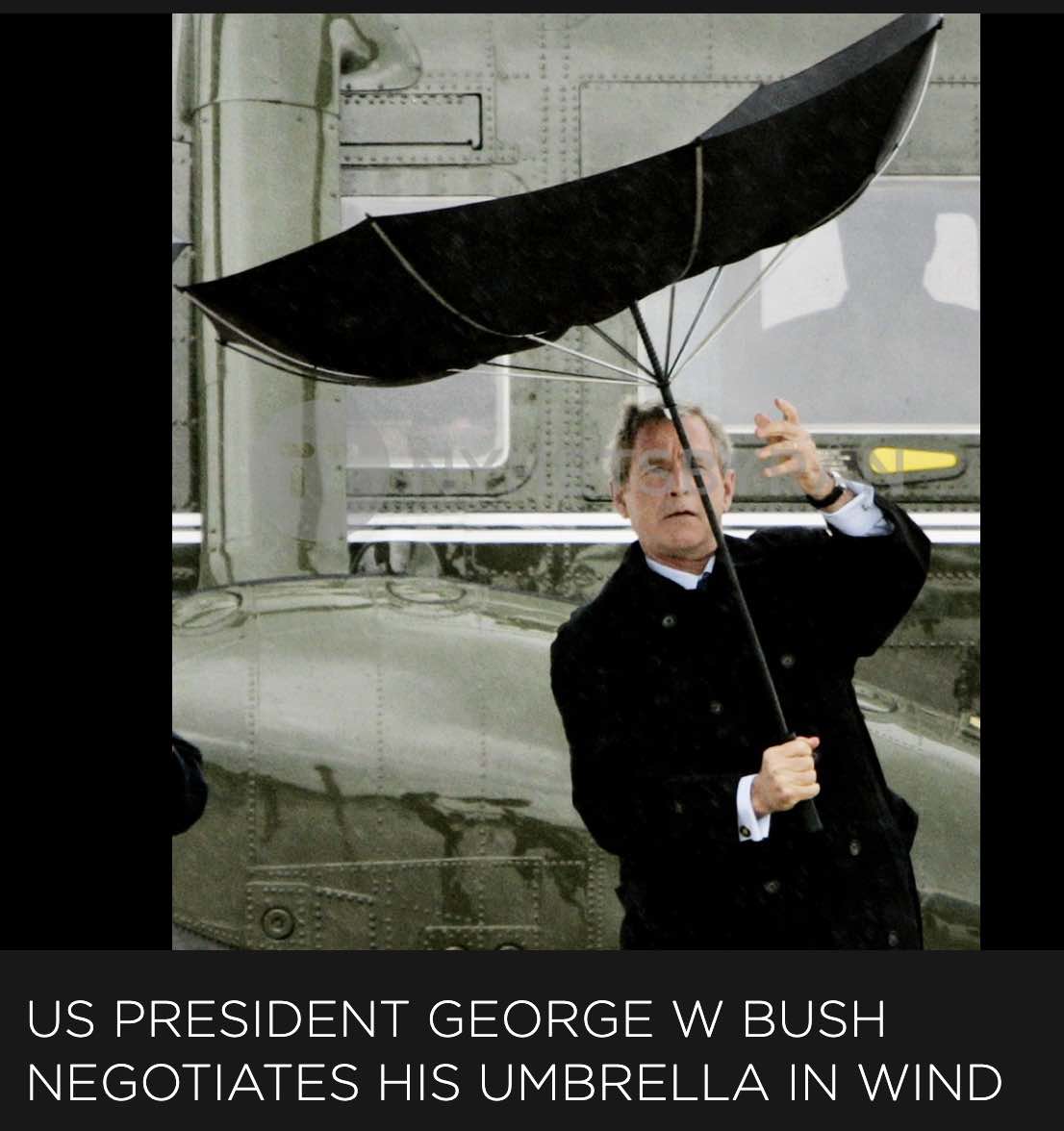

As the carbon-nucleophile bond strengthens and the carbon-leaving group bond weakens, the geometry of the carbon becomes inverted, like the proverbial umbrella in a strong wind. This is generally not noticeable unless the alkyl halide carbon is a chiral center.

3. Primary and Methyl Alkyl Halides Work Best

The Williamson works best for primary and methyl alkyl halides. Let’s look at some examples:

Note that the third example the stereochemistry of the C-O bond is unaffected. That’s because it’s only the geometry of the electrophile (i.e. the alkyl halide) in the SN2 that becomes inverted.

If the alkyl halide carbon is chiral, inversion can occur, as it does for this secondary alkyl halide below.

Since alkoxides are strong bases, there will be significant competition between SN2 and E2 reactions with secondary alkyl halides. Alkenes and ethers are generally obtained as mixtures. [Note 2].

With tertiary alkyl halides, the Williamson ether reaction fails completely, and only alkenes are obtained.

Since SN2 and E2 reactions generally do not occur with sp2 hybridized carbons, another case where Williamson reactions fail is with aryl and alkenyl halides.

4. Choice of Solvent For Ether Formation

A common choice of solvent for the Williamson is to use the parent alcohol of the alkoxide, such as ethanol when using sodium ethoxide.

It is generally a bad idea to use an alcoholic solvent that is not the conjugate acid of the alkoxide, as discussed in the quiz below:

When using sodium hydride (NaH) or potassium hydride (KH) a common choice of solvent is ethers such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), diethyl ether, or polar aprotic solvents such as dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO).

5. Intramolecular Williamson Reactions

If an alcohol and alkyl halide are present on the same molecule, there is the potential for an intramolecular Williamson ether reaction to occur.

This will result in a new ring.

Ring formation is best for 5- and 6-membered rings. [Note 3 ]

The mechanism for the intramolecular Williamson reaction is identical to that for a normal SN2; it just looks weird the first time you see it.

See if you can draw the mechanism:

It’s also valuable to be able to work backwards from a final product to propose plausible starting materials. See if you can draw a feasible starting material that will result in the Williamson product below:

6. Planning Syntheses of Ethers via The Williamson

All right. Given all we have said about the Williamson, let’s see some examples of using this reaction to plan some syntheses of ethers.

With any ether there are two potential sites where a new C-O bond could be formed, which gives you two alkyl halide + alkoxide combinations to choose from.

Let’s start with a fairly easy example. See if you can come up with reasonable starting materials for the synthesis of propyl methyl ether via the Williamson reaction.

Note that for our purposes it doesn’t matter whether you choose Cl, Br, I or another good leaving group for your alkyl halide/sulfonate, so long that it isn’t F.

With propyl methyl ether, there are actually two good choices for building the ether. You can either use propyl halide (primary) with methoxide, or methyl halide (methyl) with propoxide. Both of these SN2 reactions should work well.

Since elimination is absolutely impossible on methyl, I’d give a slight preference to using the propoxide/CH3Br combination, but either one would work.

Ready for the next one? See if you can come up with a plan for the ether below:

Working backwards gives us two sets of reactants. The one that will work best will be the alkoxide of the secondary alcohol with a methyl halide, since SN2 reactions are fastest on methyl groups and elimination reactions (E2) are impossible and will not compete.

A worse choice would be a secondary alkyl halide with methoxide. Note that since this is an SN2 - which proceeds with inversion of configuration - and the secondary alkyl halide chiral, the starting alkyl halide will have the opposite configuration to that of the starting material.

Let’s try t-butyl ethyl ether next.

Our two choices of reactants include

- A tertiary alkoxide with a primary alkyl halide

- A tertiary alkyl halide with a primary alkoxide

Hopefully by now it should be clear that the first choice is best, since primary alkyl halides are excellent substrates for SN2 reactions and tertiary alkyl halides are not.

Even though the alkoxide is tertiary, the reaction should still work fairly well. Being bulky, there will be more elimination (E2) than normal, but this could be minimized by keeping the reaction temperature relatively low. [See article: Bulky Bases In Elimination Reactions]

Our final quiz asks how to synthesize phenyl methyl ether.

Our choices are:

- A methyl halide with a phenyl alkoxide

- An aryl halide with methoxide

Again, there is a very clear good choice here, as sp2 hybridized carbons (aryl halides) do not undergo SN2 reactions (just try doing a backside attack inside that phenyl ring!). In constrast, the reaction between the phenoxide and CH3Br should work much better without any complication.

7. Summary

So what are the key takeaways here?

If you’ve already learned the SN2 reaction, this should mainly be a refresher.

- SN2 reactions work well for methyl and primary alkyl halides, don’t work for tertiary, alkenyl or aryl halides, and are pretty borderline for secondary alkyl halides.

- Make sure you are familiar with drawing intramolecular examples of this reaction, because instructors tend to love throwing these types of mechanisms at you on exams.

- Get comfortable with planning the synthesis of ethers through Williamson reactions. There will generally be two alkoxide/alkyl halide combinations to choose from. Choose the best SN2 reaction available.

There are situations where the Williamson is not the best choice for ether synthesis and we must resort to other methods. For more, see Ethers From Alkenes, Tertiary Alkyl Halides, and Oxymercuration.

Notes

The contents of a separate article, “The Williamson Ether Synthesis - Planning” has been combined into this article - Sept 2023.

Note 1 - [Background rate of SN2]

Note 2 - [Secondary alkyl halide]

Note 3 - A Final Note About Rates of Ring Formation

I should end with a cautionary note about reactions that lead to ring formation. One question that comes up a lot is, “when do I know when a new ring will form?” [Shortcut spoiler: yes to 5 and 6 (and 3), generally “no” to rings 7 and above]

Great question! This is one of those issues that makes organic chemistry “hard” for the beginner, but “deep” and “interesting” for the lifelong practitioner because there are several key factors that often work in opposite directions.

First of all: Not all rings form at the same rate. That is, the rate at which a ring will form is, to some extent, dependent on the length of the chain.

How does this fit in with what we already know about substitution reactions?

Remember that the rate of a substitution reaction is proportional to the concentration of nucleophile and the concentration of electrophile. But what happens when the nucleophile and electrophile are on the same molecule? For this we use a concept called “effective concentration” which is to say that the reaction rate will be related to how much time the nucleophile spends in the vicinity of the electrophile. There isn’t space to go into this in detail in this post, but let’s use this velcro straps on this shoe as an overly simplistic example.

If the velcro straps are too short, then the nucleophile (strap) can’t reach the electrophile (on the shoe). If the velcro straps are too long (imagine if they were each a foot long, for instance!) , then the shoes will be annoying to put on because of the decreasing likelihood that the nucleophile will be in the vicinity of the electrophile (an example of low “effective concentration”). The rate of formation for very large rings will approach the rate of intermolecular reactions.

Of course molecules are more complicated than belts (or velcro straps) because of the ideal 109° angles of tetrahedral carbons. That creates some additional complexity, notably the issue of ring strain.

For example you are probably aware by this point that 3 and 4 membered rings are quite strained, whereas rings of size 5, 6, and 7 are relatively unstrained. [See article - Ring Strain in Cyclopropane and Cyclobutane]

If you’re just starting out you’re likely unaware that rings of size 8-11 are strained for a very interesting reason (transannular strain) and then rings of size 12 and above are generally unstrained.

For a student in an introductory course, a good rule of thumb is: Formation of 5 and 6 membered rings is fast. Formation of rings of size 7 and above is slow. As for the smaller ring sizes, we’ve seen examples where 3 membered rings form (from halohydrins). Seen less often, but also fast is the formation of 4 membered rings.

This is a vague generalization. “Give me numbers!” you might be saying. My copy of March says the following. Note that this is for a different reaction than the Williamson ether synthesis [formation of cyclic esters through SN2 of carboxylates with alkyl halides], but the trend should hold.

For a more quantitative approach, I suggest you look into this paper on ring closure kinetics.

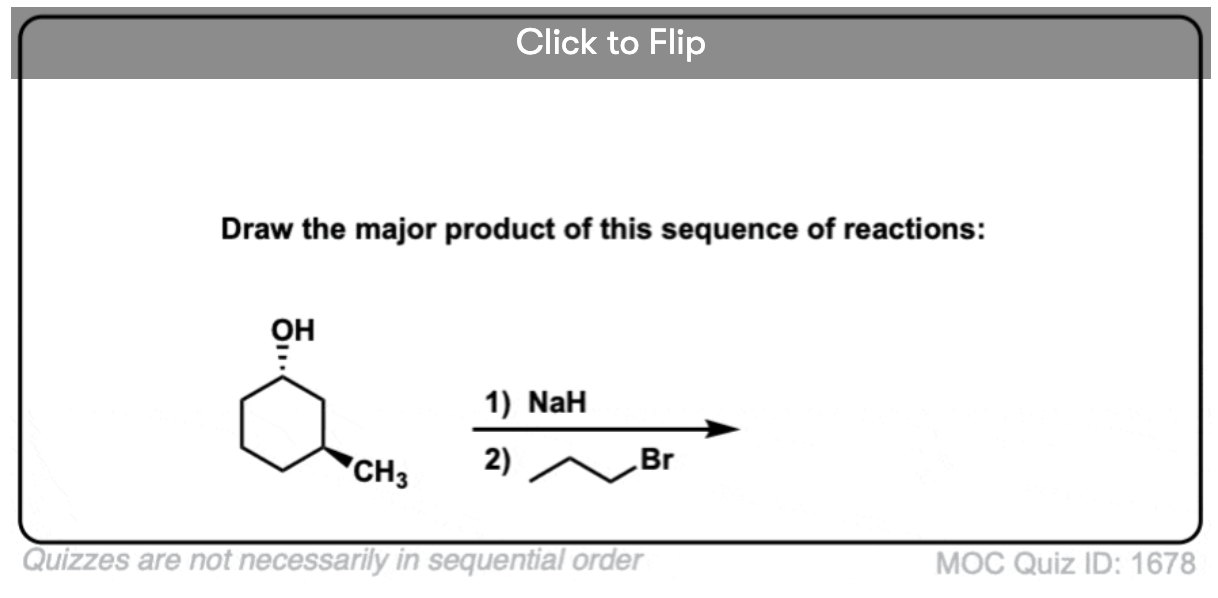

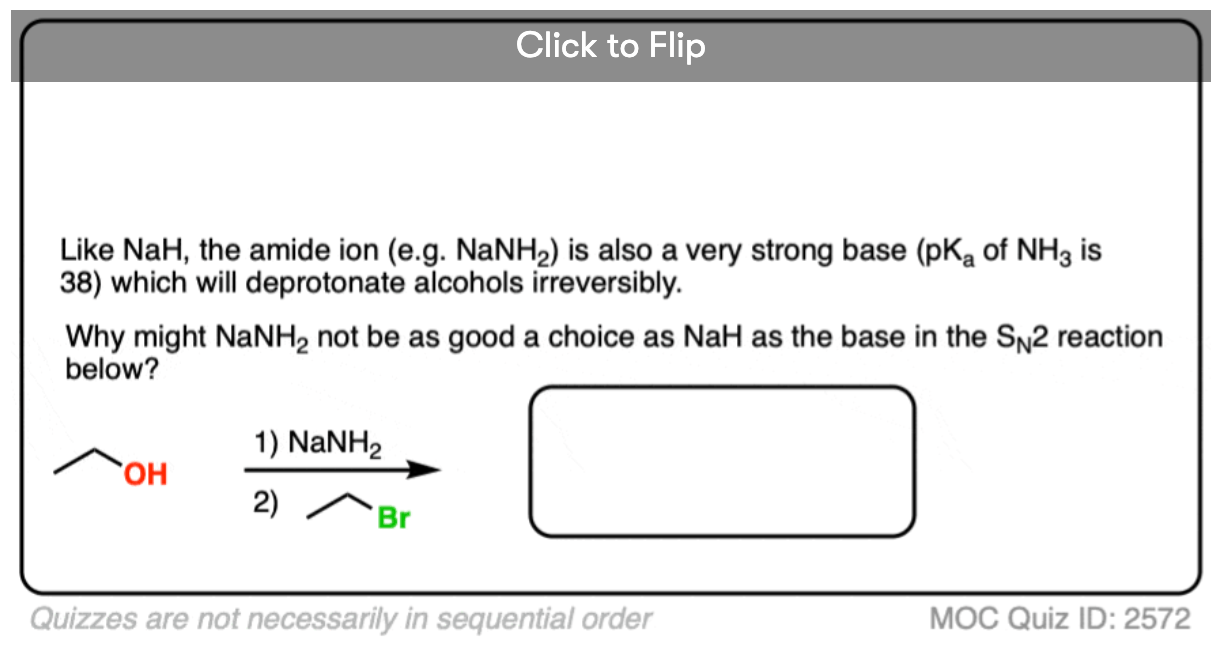

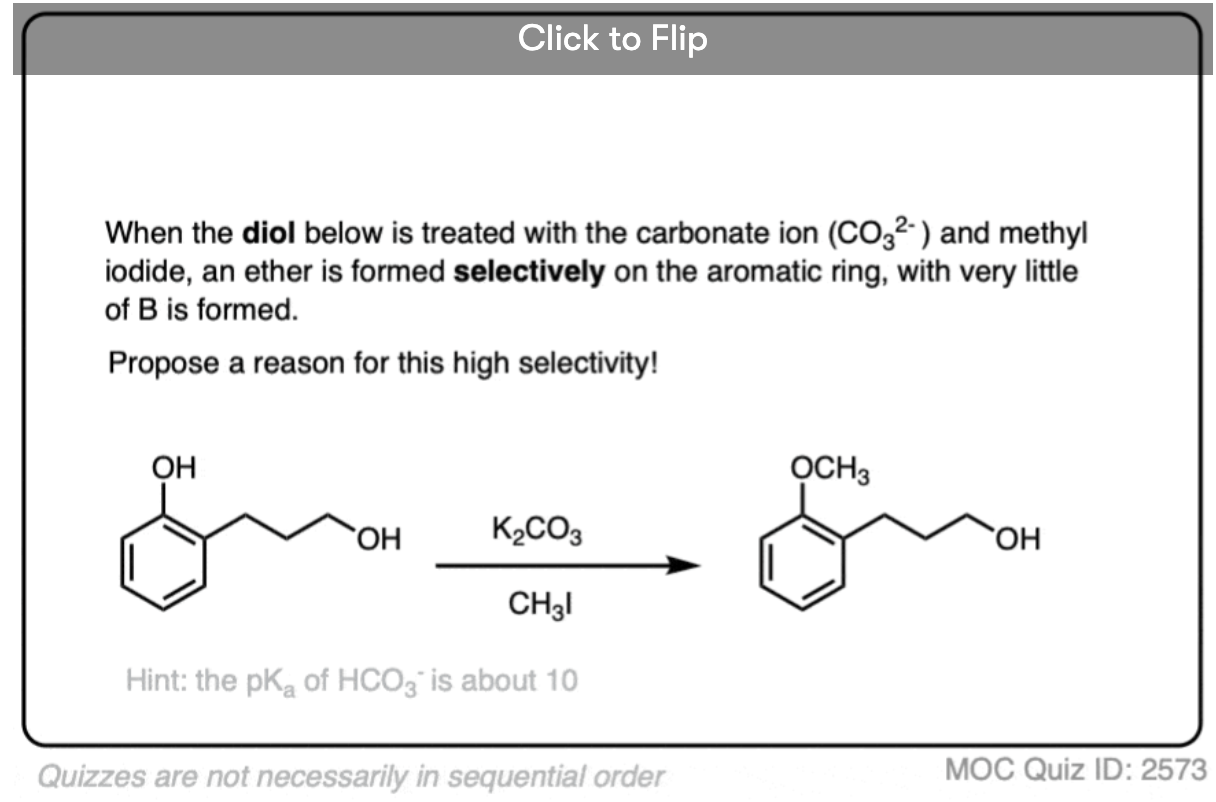

Quiz Yourself!

Become a MOC member to see the clickable quiz with answers on the back.

Become a MOC member to see the clickable quiz with answers on the back.

Become a MOC member to see the clickable quiz with answers on the back.

Become a MOC member to see the clickable quiz with answers on the back.

Become a MOC member to see the clickable quiz with answers on the back.

Become a MOC member to see the clickable quiz with answers on the back.

(Advanced) References and Further Reading

- XLV. Theory of ætherification. Alexander Williamson (1850) , The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, 37:251, 350-356, DOI: 080/14786445008646627 The original Williamson paper. When Williamson reported the reaction in 1850 he didn’t know what an SN2 was - scientists didn’t even know what electrons were, for that matter - which again goes to show that the science of organic chemistry developed through a lot of empirical observations first, and the theory developed later.

- Equilenin 3-Benzyl Ether M. Hoehn, Clifford R. Dorn, and Bernard A. Nelson The Journal of Organic Chemistry 1965 30 (1), 316-316 DOI: DOI: 10.1021/jo01012a520 One of the reactions in this paper is a classic Williamson reaction - protection of the alcohol in dehydroestrone as a benzyl ether, using benzyl chloride.

- Total Synthesis of (+)-7-Deoxypancratistatin: A Radical Cyclization Approach Gary E. Keck, Stanton F. McHardy, and Jerry A. MurryJournal of the American Chemical Society 1995 117 (27), 7289-7290 DOI: 1021/ja00132a047 In modern organic synthesis, the Williamson reaction is used for the protection of reactive alcohols in a substrate. Common protecting groups include methoxymethyl (MOM) and 2-methoxyethoxymethyl (MEM). MOM protection is employed in this total synthesis by Prof. Keck and coworkers.