Teacherhead

I used to be Deputy Head at Alexandra Park School in Haringey. We opened the school in 1999 with just 162 Year 7s and 11 members of staff. We called ourselves ‘The First XI’ for a while..until the staff who joined later got sick of it! For the first few years, while we could afford it, we ran a two-day residential for all staff where we engaged in a superb process of ethos-building and strategic thinking. It played an important role in creating a strong collective view of pedagogy, attitudes to discipline, inclusion, aspirations and many other things.

At the very first event we worked on a common view of what learning should look like. Interestingly, our instinct was not to focus on individual lessons. We did not try to agree what a good lesson would be like except in terms of routines for behaviour management; our instinct was to think about units of work - the overall learning experience across many lessons. In our list, we agreed that a typical unit of work should include the following:

- Whole-class teaching: This was core.

“This is an essential element in providing cohesion to differentiated, multi-task schemes of work and providing a sense of inclusiveness for all students within mixed ability classes. Direct whole-class teaching enables students to develop the skills required for questioning, problem solving and listening to others’ ideas. Core concepts are often best learned through whole-class teaching.” True in 1999; true today.

- Opportunities for students to engage in group work and to work individually

- An element of choice or control

- A creative element wherever possible

- Opportunities for all students to make presentations, contributing orally as well as to produce extended writing.

- Assessment and feedback that would inform subsequent learning

- Homework and independent research.

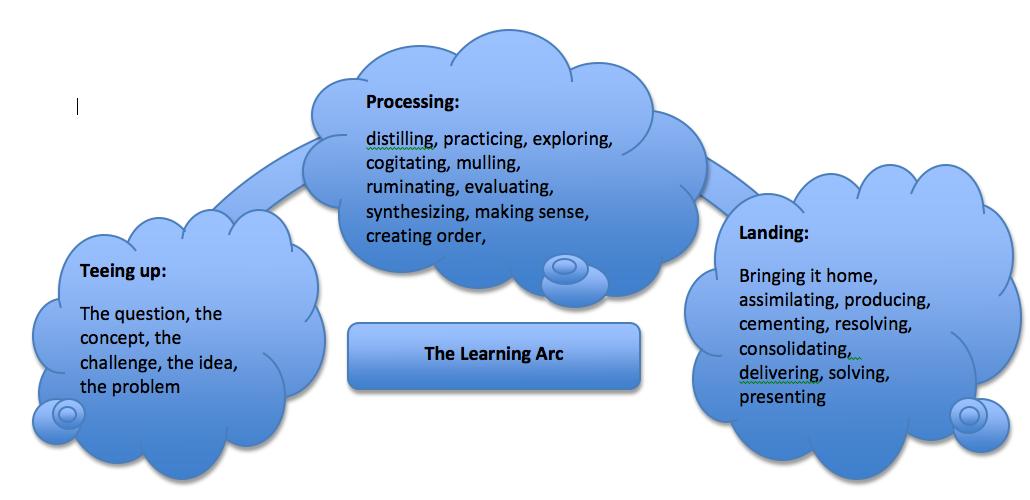

And so on. We also discussed general issues around differentiation, literacy and numeracy and high expectations, but the idea was very explicitly that a healthy balance of learning experiences should be planned for across a series of lessons. That now seems at odds with the narrow lesson snapshot culture that is drowning many schools where teachers obsess about what one single lesson should be like. However, it chimes in with the ideas I’ve expressed before about The Learning Arc:

Learning takes the time it takes and varies significantly from student to student, concept to concept and skill to skill. Then, there is the idea of the ‘Learning Journey’ that is personal to each student. As I’ve discussed in my Great Lessons post on Journeys, any one lesson must take account of prior learning, the learning that comes next and the real life context in which students exist. A series of lessons is linked together but the detail of each lesson should really be contingent on the learning that has taken place and an assessment of how far there is still to go towards some learning goals.

In this context, homework - or more generally, the learning that happens between lessons - is as much part of the process as the lessons themselves.

Then there is the notion of variety in general that I discuss in the post using the fairly obvious balanced diet metaphor. There is no one way to teach or to learn. How are we to know what works best exactly? It is very difficult, however well informed we are with the latest evidence. By engaging a range of learning modes, we are not just mixing it up for a bit of light novelty and soft engagement - we are doing it because learning is multi-dimensional and requires multiple lines of attack if every student is going to make maximum progress. There will never be THE idealised learning mode - any more than a tube of nutrients equates to a good healthy meal that you’d want to eat again.

So, a given sequence of lessons might have a number of variants within it:

- A lesson where you set out some learning objectives for the series to follow… meaning that you don’t keep having to do this in every lesson that follows beyond making references as required.

- Any number of lessons featuring teacher-led exposition of some key ideas, some verbal question and answer, then a period of individual work on written answers.

- An activity which requires students to work together to solve problems, pooling their ideas and challenging each other before presenting solutions to the class. This could be extended into more elaborate groupwork strategies like experts and envoys.

- A lesson where students bring in their answers to questions completed for homework and the lesson is driven by self assessment and a process of going through common difficulties and questions.

- A lesson were books are handed back after being marked, giving time for everyone to act on the feedback that has been recorded.

- A lesson where multiple inputs are considered and explored - poems, paintings, historical sources, geographical charts and graphs, science phenomena through front-bench demonstrations - but no responses are produced.

- Lessons were a text is read aloud, a video is watched, a story is told, a student explains their ideas based on their individual research.

- A lesson were, reflecting on the inputs presented in previous lessons, students get their heads down to an extended bit of analysis, or writing or painting for nearly the whole time.

- A lesson where students are given some skeletal instructions before exploring an unknown idea - perhaps a maths investigation or a science practical or a previously unseen poem - before the learning points are revealed and consolidated.

- A feedback session where final submissions are presented and subjected to peer review against some success criteria.

I could go on…. and on and on and on and on. The point is that none of these activities stands alone; they are interwoven, interlinked and all contribute to the learning process in some way. Some lessons will contain multiple elements, some won’t - because they don’t need to.

I think this has consequences for our psychology around developing our practice and evaluating the quality of teaching and learning. Firstly, don’t plan one-offs; think about a range of possible lesson modes that you might employ over time, ready to adjust in accordance with students’ responses. You can’t pack it all in to every lesson but over time you can.

Secondly, if you drop in on a lesson that is part of a sequence, you need to ask some questions:

- Where does the lesson fit into a sequence? Where are they along the arc?

- Is this learning activity compatible with an overall process that could lead to strong outcomes?

- Is it reasonable for progress to be evident within this lesson or might I need to see what happens over the next week or so?

- What general attitudes and dispositions are being modeled by teacher and students? Do they indicate positive learning-focused relationships compatible with an overall process that leads to strong outcomes?

- Does the record of work in books and folders, with the feedback dialogue alongside the work itself, tell a better story than the content of the one-off performance in front of you?

And so on…

As I’ve outlined in this post about our latest attempt to capture the bigger picture in our evaluation processes, standardised lesson templates and one-off lesson observations are very limited in value. We need more points of reference. Teachers need to have the confidence to plan lesson sequences where learning and progress are evidenced over time, not in artificial bite-sizes just to satisfy the accountability process. Learning can be deep and slow and we need to be very conscious not to promote fast and shallow as the alternative. And that means that in some lessons, you might not see exactly what learning is going on at all; you might have to come back later. Much later. And that is completely legitimate.

Link nội dung: https://studyenglish.edu.vn/index.php/how-many-lessons-are-you-going-to-learn-next-month-a85715.html